A still life from the Dutch Golden Age

Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Leihgabe des Pinakotheks-Vereins 🔍 Über das Bild mit der Maus fahren, um zu vergrößern

Bathed in a mysterious glow, an exquisite porcelain jug and a glass goblet with wine glinting inside appear against the semi-darkness of a window alcove. In the foreground are a half-peeled lemon, an open pomegranate, and some velvety peaches. The Dutch baroque painter Willem Kalf masterfully demonstrates how the surfaces reflect the light in different ways. This still life can be admired at the Alte Pinakothek museum in Munich.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

It once belonged to the painter Josef Block.

In the Munich Art Scene

Block moved to Munich as a young man in 1881. He was originally from Silesia, began to study art in Breslau (Wrocław) and continued his studies at the Kunstakademie (Academy of Fine Arts) in Munich.

Gemeinfrei, via Wikimedia Commons

One of his tutors was Bruno Piglhein, a painter of historical scenes. Piglhein arranged a prestigious job for his student: Block was allowed to contribute to Piglhein’s monumental panorama Jerusalem am Tag der Kreuzigung Christi (Jerusalem on the Day of the Day of Christ’s Crucifixion). The panorama, which went on display for the first time in 1886 in Munich, was destroyed in a fire in Vienna in 1892.

Stadtarchiv München DE-1992-FS-NL-PETT1-3651 Creative commons 4.0

Josef Block set up a studio at 75 Theresienstraße. This part of Munich – around the neighborhoods of Maxvorstadt and Schwabing – had a population largely made up of artists, students, and academics. Josef Block lived in the same building as two other painters, Fritz von Uhde and Ludwig Dill.

„Death to the studio tone, kitsch, and falsity"

Bildarchiv Foto Marburg, Bilddatei-Nr. fm121564

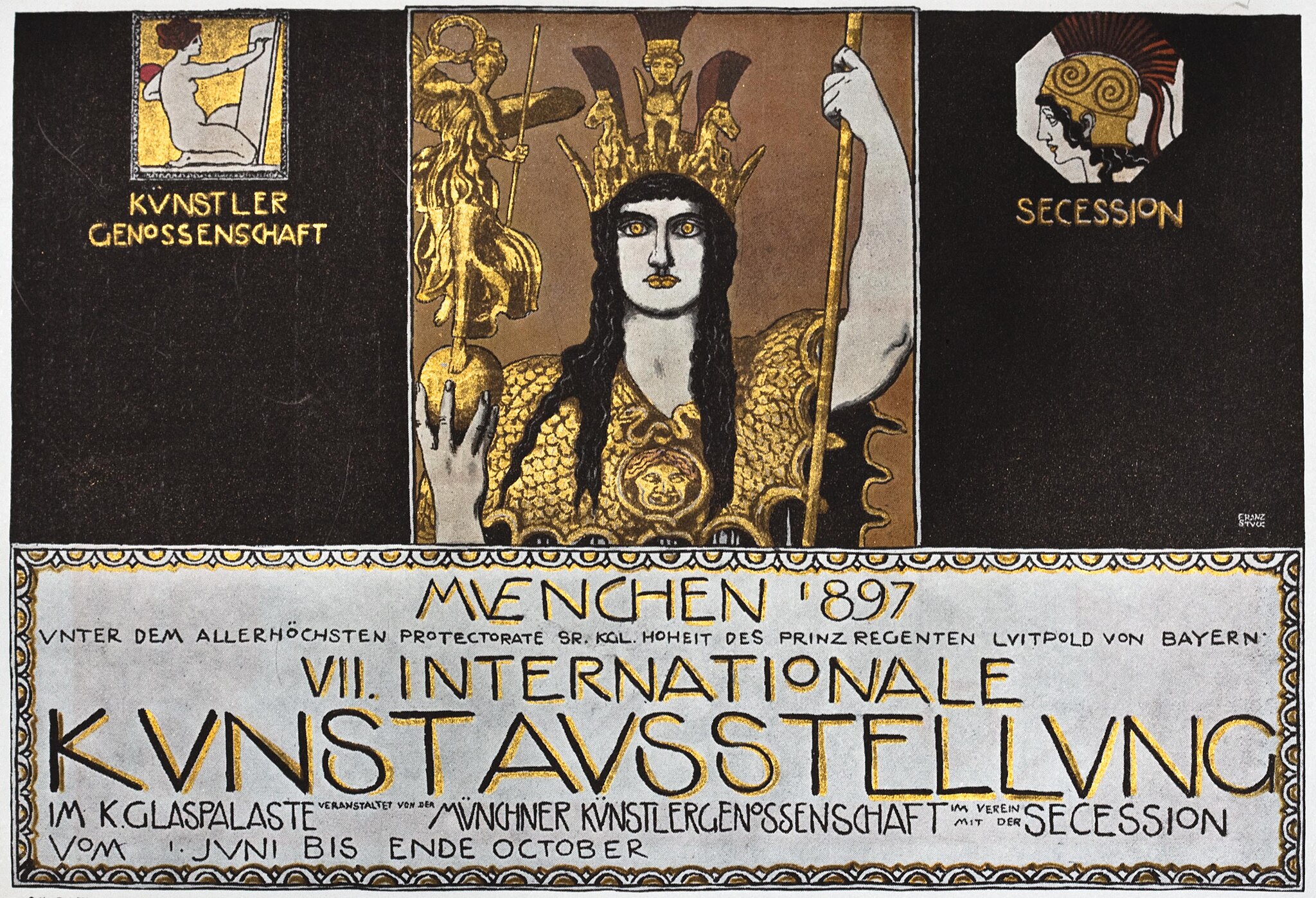

It was in this studio that on April 4, 1892 Block and 95 fellow artists founded the „Verein bildender Künstler Münchens e.V.” (Munich Association of Visual Artists), which later became famous as the „Secession”. This group considered itself the antithesis of the established art scene in Munich, which was dominated by the portraitist Franz von Lenbach. The co-founders of the Secession were Block’s professor Bruno Piglhein and the “prince of painting” Franz von Stuck. Author Margarete Mauthner recalled the foundation of the movement: „Secession? – The word meant nothing to me; it was an alien concept. But when I heard the names of those behind the movement, it all became clear: light, freedom, purity in art, even when it did not follow an entirely new direction, death to the studio tone, kitsch, and falsity…”

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Block was an active contributor to the exhibitions of the Munich Secession. His paintings were exhibited in Germany and abroad. They were lauded by critics: „Block’s paintings reveal multiple, subtle narratives, in muted colors, in the modern style characterized by broken sentences and dashes.”

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

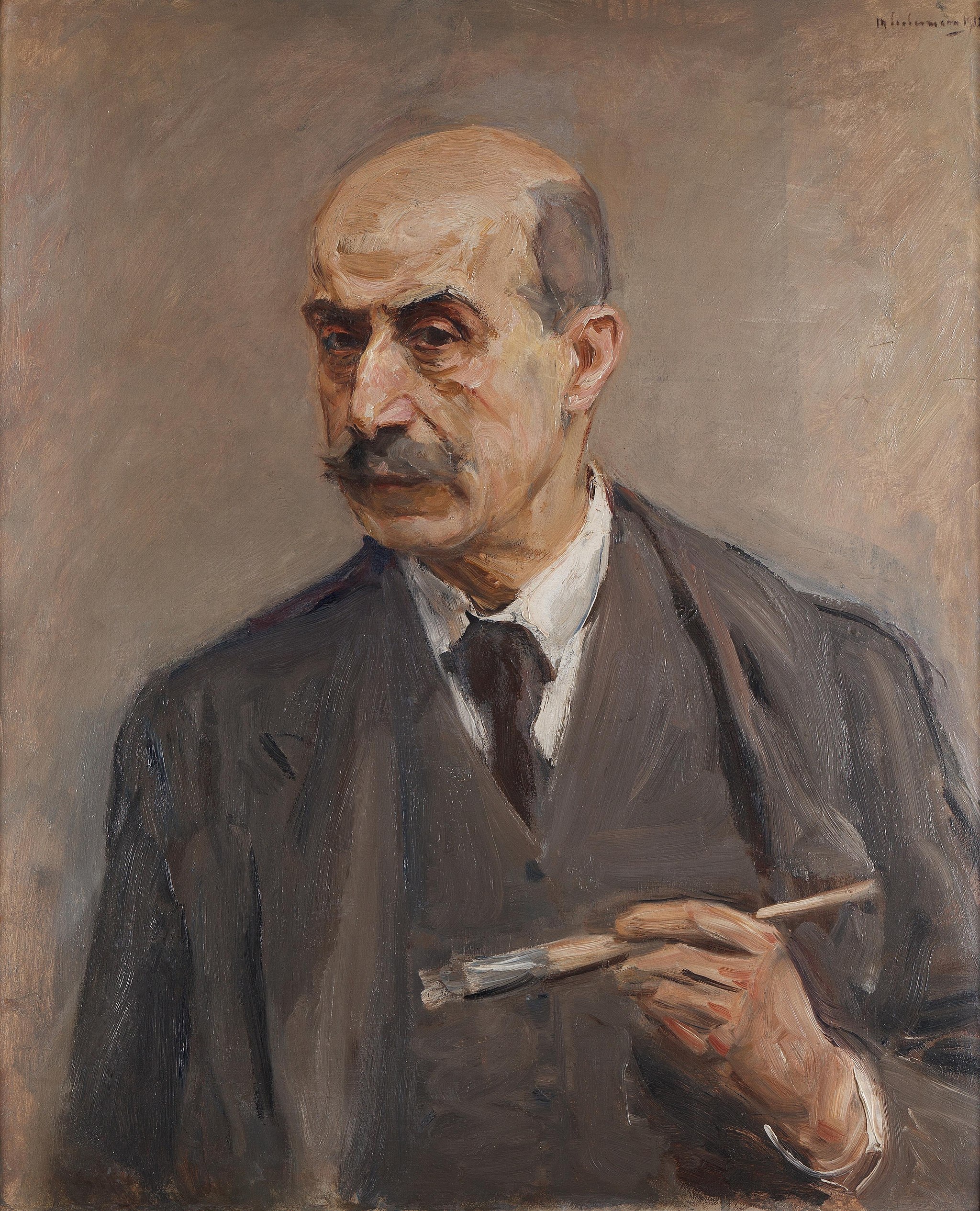

Soon after the momentous gathering in his studio, Block left Munich and moved to Berlin. He was a co-founder of the Berlin Secession in 1898, a movement led by Max Liebermann.

Familienarchiv Block

He married Else Oppenheim, the daughter of the banker Hugo Otto Oppenheim and his wife Margarete, née Mendelssohn. The couple soon added to their family with the birth of Anna Luise, Hugo, and Otto. However, for a long time, they were unable to enjoy family life as Else suffered severe depression and had to be admitted to a psychiatric institution in 1903.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-1986-0718-502.

Josef Block became firmly established in the art world of Berlin, as he had been in Munich. He was friends with Max Slevogt, Emil Orlik, and Max Liebermann and became a sought-after portrait artist in high society. Prominent art dealers such as Fritz Gurlitt and Paul Cassirer sold his works and he often took part in the Biennale in Venice and Secession exhibitions.

Berliner Leben – Zeitschrift für Schönheit und Kunst, 1904

In 1904 the women’s illustrated magazine Berliner Leben – Zeitschrift für Schönheit und Kunst (Berlin Life – Magazine for Beauty and Art) wrote: “The artist is at the center of his works; he has a calm and self-assured gaze. A renowned painter who has a very good name in the art world. Here you can see Die Versuchung des heiligen Antonius (The Temptation of Saint Antony), underneath it Spanierin (Spanish Woman), above this to the right another picture of a Spanish woman, and below that Dame im Grünen (Woman in the Greenery); in addition, the Grablegung Christi (Burial of Christ) and Chansonette (Little Song).”

Familienarchiv Block

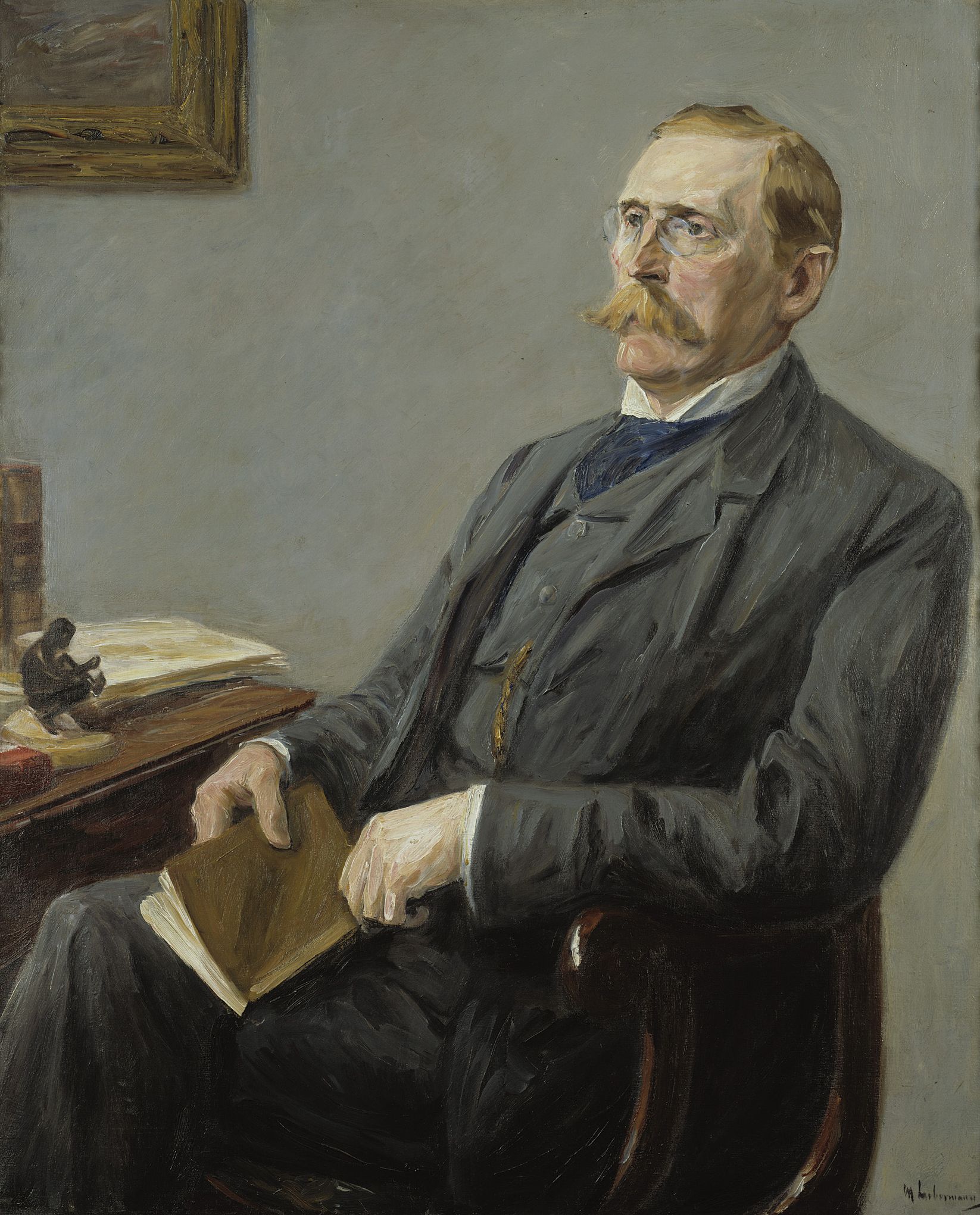

Block had a longstanding friendship with the writer Gerhart Hauptmann, whom he had known since his time in Breslau. Block often visited Hauptmann on the Baltic Sea island of Hiddensee and in the Giant Mountains. He produced a series of portraits of Hauptmann during this period.

Familienarchiv Block

Block was a keen and frequent traveler. Around the turn of the 19th / 20th century, he embarked on a grand tour of the Mediterranean, which took him as far as Egypt. In the 1920s he often visited Italy, Switzerland, and France. He always had his camera with him – he was a fan of the new artistic medium of photography.

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie / Jörg P. Anders Public Domain Mark 1.0

Around 1906 Block inherited a collection of Old Masters paintings from his uncle, the Berlin lawyer Berthold Richter. The paintings were so famous and so valuable that in 1919 leading representatives of the museums in Berlin such as Wilhelm von Bode wanted to include them in an inventory of national treasures.

Familienarchiv Block

From the late 1920s Josef Block lived in a large apartment at Derfflingerstraße in Berlin-Tiergarten.

„Mr Block’s apartment was like a museum”, recalled his housekeeper, Gertrud Lessow. „There were pieces of genuine period furniture, the precious rugs were literally laid one on top of the other. The series of high-ceilinged rooms which had no connecting doors were full of valuable porcelain, sculptures, pictures, bronzes…”

Targeted art theft by Göring’s lead buyer

U.S. Army Signal Corps, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

After the National Socialists assumed power, Josef Block was subject to discriminatory taxation because he was Jewish. He then became the victim of targeted art theft. Art dealer Walter Andreas Hofer possibly became aware of Block’s art collection through the inventory of national cultural treasures. Hofer was Hermann Göring’s lead buyer and built up his art collection. In 1939 he made Josef Block sell him two of the pictures from the collection he had inherited: a still life by Willem Kalf and a painting by van Beyeren.

Familienarchiv Block

Gertrud Lessow wrote: „I can still remember how devastated Mr. Block was at the time when the two pictures were taken from him under duress. He had wanted to keep them as a legacy, but also because they belonged in his collection.”

Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen

Göring was interested in the van Beyeren painting and Ernst Buchner, director general of the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen (Bavarian State Painting Collections) in the one by Kalf. Buchner offered Hofer two paintings in exchange. This is how the still life came to be in the Alte Pinakothek museum in Munich.

Herbert Sonnenfeld, view of the main building of the Jewish Hospital in Berlin, 2 Iranische Straße, around 1935; Jüdisches Museum Berlin, inv. no. FOT 88/500/267/013, purchased with funds from the Stiftung Deutsche Klassenlotterie (German Lottery Foundation), Berlin

Final residence in a ,Jew house’

In 1943 Josef Block received a deportation order. Gertrud Lessow described the situation: „He was very ill and bedridden and so by intervening directly [with the authorities] I was able to spare him from deportation. However, he had to vacate his apartment and move into a ‘Jew house’ [Judenhaus, collective accommodation assigned to Jews].”

Block’s final address was the Jewish Hospital, which the National Socialists had turned into a ‘Jew house’ and an assembly camp for Jews who were to be deported from Berlin. Even under these circumstances Josef Block was very productive. He began work on a portrait of a Jewish physician. However, he never completed it. The painter died on December 20, 1943. The urn with his ashes was interred in the Jewish cemetery at Berlin-Weißensee. stirbt am 20. Dezember 1943. Die Urne mit seiner Asche wird auf dem Jüdischen Friedhof in Berlin-Weißensee beigesetzt.

Josef Block's house in Derfflingerstraße was destroyed by fire after the end of the war. Not only parts of Block's art collection burned, but also most of his own work.

Restitution to Josef Block’s grandson

Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen

In 2008 the painting by Kalf was restituted to the painter’s grandson, Peter Block.

„It means a lot to me that the injustice done to my grandfather has been acknowledged and that the crimes of the Nazi era are remembered in the process”, said the heir. “In addition, I also felt it necessary for this wonderful still life by Kalf to remain on public view in the Alte Pinakothek.” For this reason, he agreed to sell the work to the Pinakotheks-Verein (Pinakothek Association), which has made it available to the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen on a permanent loan. And so today visitors to the Alte Pinakothek can continue to admire this magnificent work from the Dutch Golden age.